-

- The two swimmers carefully pushed their

water-proof wrapped bundles onto the sloping riverbank and slipped

silently out of the water. Shaking themselves like dogs to rid their

bodies of as much water as possible, they hurriedly donned the clothes

that were secured to the top of the bundles. For some time before

darkness fell they had lain hidden on the opposite riverbank, timing the

frequency of any border

guard

patrols and choosing a landing area on the other side. Although the

river was not particularly wide at this point, the current was

reasonably strong and rather than fight it they planned to allow the

current to aid them in a diagonal crossing. Dressed, they hoisted the

packs by the rope harness, adjusted them on their backs, and set off for

the pre-arranged rendezvous with their colleagues. They had some ten

kilometers to cover during the short hours of summer darkness, avoiding

any military patrols enroute. guard

patrols and choosing a landing area on the other side. Although the

river was not particularly wide at this point, the current was

reasonably strong and rather than fight it they planned to allow the

current to aid them in a diagonal crossing. Dressed, they hoisted the

packs by the rope harness, adjusted them on their backs, and set off for

the pre-arranged rendezvous with their colleagues. They had some ten

kilometers to cover during the short hours of summer darkness, avoiding

any military patrols enroute.

- The year was 1899, the country was

Lithuania, the river was the Sesupe, which at that point was the border

between East Prussia and Lithuania, before it merged with the Nemunas,

Lithuania's largest river, which then became the border. The two

swimmers were my father, Vincentas (Vincas) Stepsis, and my uncle

Juozas, both of whom were smugglers - in the literal sense of the word -

as the bundles they carried, according to the occupying Imperial Russian

authorities, contained illegal material. However, the contraband they

carried across the frontier of the two countries was not to evade

revenue payable on taxable commodities, nor were they doing so for

personal gain

or profit. They were risking their lives, incarceration, or banishment

to the frozen wastes of Siberia for nothing more than Lithuanian

language literature - books, journals, newspapers - which would be

secretly disseminated to their fellow countrymen; the hazardous task

voluntarily undertaken without any thought of gain or glory.

- But why was it necessary to bring their

own-language literature into the country covertly and at the risk of

life and limb? Why would ordinary country - folk - peasants - at best

only semi-literate undertake such risky, dangerous missions for the sake

of printed paper? Why, indeed, had this to be done clandestinely and why

was apprehension by the Russian authority so severely punished? To

comprehend the why and the wherefore thousands of people like Vincas and

Juozas Stepsis gladly did this task, despite the consequent hazards, it

is necessary to understand something of the troubled history of the

ancient land of Lithuania. By virtue of a 16th century treaty with

Poland, a "Commonwealth of Two Nations" had lasted more than

two hundred years until the Third Partition of the Commonwealth in 1795

resulted in Lithuania being seized by Imperial Russia. During the 19th

century, as with most occupied and subjugated countries, there were

uprisings and insurrections against the occupying authority. After the

1863 insurrection was quashed, Tsar Alexander the Second imposed the

most stringent of measures on Lithuania and its people. He installed a

Governor General, one Mikhail Nikolaevich Muravyov, with instructions to

produce a Lithuania "with nothing Lithuanian in it." Muravyov

began his implementation of the Tsar's orders by proclaiming a complete

ban on the Lithuanian press,

the

usage of the Latin alphabet and the Lithuanian language - only the

Cyrillic alphabet and Russian language were to be used and taught. In

essence everything Lithuanian - language, culture, the

usage of the Latin alphabet and the Lithuanian language - only the

Cyrillic alphabet and Russian language were to be used and taught. In

essence everything Lithuanian - language, culture,

religion - was proscribed, and so severe were the penalties for

contravention that, during his time as Governor-General (till March

1865) Muravyov became known as the "Hangman of Lithuania."

- The period from 1864 to 1904 when the ban

was lifted, made the native Lithuanian press nonexistent resulting in an

unrelenting struggle to restore it. In all of European history Lithuania

is the prime instance of an occupying authority denying a former

independent nation its language and press and a people's forty-year

battle against a foreign language and culture being forced upon them. It

is no wonder that the time of the prohibition became known in Lithuania

as the "Forty Years of Darkness."

- An underground movement began printing the

forbidden literature in their native tongue across the border in East

Prussia. Originally inspired by the clergy, particularly Bishop Motiejus

Valancius whose rallying call was "Visada ir visur buk

lietuvis" ("Always and everywhere be Lithuanian") and who

exhorted everyone to discard the Russian books and keep teaching the old

Lithuanian language, even if in secret. In answer to his call, men who

were themselves unable to read or write, ferried the packages of books

across the border and distributed the contents. And so the knygnesiai

(book-carriers) came into being. The womenfolk taught the children at

their knee during the performance of the daily domestic chores. Both

Tsar Alexander and Muravyov completely underestimated the nationalism,

resilience, and stubbornness of the Lithuanian people. The more

repressive the measures they inflicted, the greater grew the resistance.

On that night in 1899, my father and my uncle Juozas delivered their

bundles to the distribution center in the village of Pilviskiai before

dawn and spent the daylight hours resting and sleeping at the house of a

friend and fellow "smuggler." As darkness fell that evening,

they made preparations to return to the Sakalupio area; having said

their farewells they set off. About two kilometers or so from their

hideaway, a figure loomed up in the gloom in front of them and the voice

of the local policeman said: "Ah! Vincai, Juozai, I would not go

home tonight." Not another word was said or needed. The brothers

understood, the military were waiting for them. Turning their footsteps

toward the Sesupe river, they swam across to the East

Prussian bank intending to lie low with their book-smuggling colleagues

until the authorities gave up the search for them.

Four weeks later word reached the brothers that they were still being

vigorously sought after, the hue and cry had not diminished as they had

hoped. After some soul searching they decided it would be disastrous to

return to Lithuania for some foreseeable time with incarceration or

Siberia as the only future facing them. The only choice was to bid

farewell to their native land, their usefulness as covert book-carriers

gone, and head west-to the land of opportunity and freedom, the United

States of America. Working their way across Prussia and Germany to the

port of Hamburg they found they had insufficient funds for the fare to

America. Almost exactly twelve months from their encounter with the

friendly policeman, the boat they were on docked at the Port of Leith,

Scotland. Vincas Stepsis was born on the 9th of July 1870, his brother

Juozas two years later, at Sakalupio Dvaras (estate), near the town of

Kudirkos Naumiestis, Lithuania, about two kilometers from the banks of

the Sesupe river, to Tadas Stepsis and his wife Petronele Barzdaityte

Stepsiene. His father Tadas (my grandfather) died when Vincas was 4

years old and my grandmother Petronele died shortly before Vincas

reached his 10th birthday. Orphaned in childhood, the two boys worked

from that early age on the Sakalupio estate where their father had been

coachman to the dvarininkas (estate owner). On reaching the age

of 21, Vincas was conscripted for military service in the Imperial

Russian Army on 12th November 1891, and posted to the 6th Battery, 3rd

Brigade Grenadiers Artillery on 10th December 1891, far away from his

homeland, in the Ukraine. Two a nd

a half years later he was lying in a bed of a military hospital in

Rostov with a fractured skull where a horse had kicked him about an inch

above his right eye. While hovering between life and death, a court of

inquiry, held at nd

a half years later he was lying in a bed of a military hospital in

Rostov with a fractured skull where a horse had kicked him about an inch

above his right eye. While hovering between life and death, a court of

inquiry, held at

his bedside, ruled that he was no longer fit for any military duties and

should be released from any further service. His discharge booklet

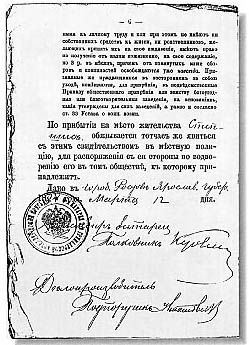

entitled "Certificate of Completion of Military Service, No.

286" says: "The bearer of this is a cannoneer, Vikenty

Tadeusovich Stepshis... after examination on 5th February 1894, the

Commission held in a military hospital recognized his incapacity to

continue military service and gave him his discharge. Stepshis is

incapable to continue either combatant or non-combatant service and so

discharged from the military service forever. Capable of private labor.

Not requiring care. At the time of his arrival at his place of

residence, Stepshis is obliged to report at the local police station

with this Certificate to reregister in his local community." On

returning home after making a complete recovery from his dreadful injury

(which the Russian Commission had thought highly unlikely), Vincas found

that his brother had not complied with his Above: The Sesupe

River, near Kudirkos Naumiestis.

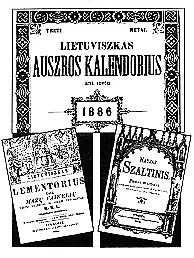

- Right:

Some of the banned books "smuggled" into Lithuania from East

Prussia by the knygnesiai. Opposite page: Last page of the

Certificate of Completion of Military Service of Vincentas Stepsis (1894).

call-up to the Russian Army but had joined the local

"underground" as a covert book-carrier. Within a week Vincas and

Juozas were a two-man unit in the team of smugglers. As border dwellers

from birth, they were familiar with the whole area and knew all the nooks

and crannies from their boyhood adventures. For the next five years the

brothers carried out their book-carrying exploits, miraculously avoiding

apprehension by the occupying authorities, until the night in 1899, when

they were, fortunately, warned allowing them to evade certain capture.

Although I was born in Scotland, my first language was Lithuanian, taught

by my mother who, unlike my father, was literate and I spent my

impressionable childhood years listening to, and begging for, tales of the

"old country"-its history, its occupation and subjugation, and

the struggles to retain the language and literature; not just told by my

father

but by his friends, like Juozas Kasulaitis, a fellow knygnesys,

when they all gathered socially in our house. A boy's eagerness for blood

and thunder stories prompted me to ask if they ever ran into trouble, were

they ever shot at by Russian soldiers when crossing the border? The short

answer was: "No, we were lucky." There were occasions as a child

when the tales I heard seemed so fantastic to me living in Scotland that I

thought they were fictional stories, like fairy tales told to satisfy a

youngster's demand for a bedtime story. Not until I visited Lithuania for

the first time in 1993, when I was welcomed as the son of a knygnesys,

did I fully realize just how understated my father's stories really were.

I still have a memento of my father's book-carrying days - my mother's

prayer book-titled "Szaltinis" ("The Wellspring") - it

has been confirmed as one of the "illegal" publications by the

Lithuanian National Archives, probably published between 1894 and 1899.

The struggles of the book-carriers have been praised in modern times by

Father Julijonas Kasperavicius who said: "The work of restoring

Lithuania's independence began, not in 1918, but rather at the time of the

book-carriers. With bundles of books and pamphlets on their backs, these

warriors were the first to start preparing the ground for independence,

the first to propagate the idea that it was imperative to throw off the

yoke of Russian oppression." In any other country a smuggler as an

ancestor would probably be cause for embarrassment but, as the son of a

Lithuanian "smuggler" of the 19th century, I have no sense of

shame or embarrassment. The very opposite, for I have a heartstirring

pride that my immediate ancestor was one of the warriors described by

Father Kasperavicius and had been a hero - however minor - of his country

and his, and his many colleagues' exploits are part of the folklore of his

native land. father

but by his friends, like Juozas Kasulaitis, a fellow knygnesys,

when they all gathered socially in our house. A boy's eagerness for blood

and thunder stories prompted me to ask if they ever ran into trouble, were

they ever shot at by Russian soldiers when crossing the border? The short

answer was: "No, we were lucky." There were occasions as a child

when the tales I heard seemed so fantastic to me living in Scotland that I

thought they were fictional stories, like fairy tales told to satisfy a

youngster's demand for a bedtime story. Not until I visited Lithuania for

the first time in 1993, when I was welcomed as the son of a knygnesys,

did I fully realize just how understated my father's stories really were.

I still have a memento of my father's book-carrying days - my mother's

prayer book-titled "Szaltinis" ("The Wellspring") - it

has been confirmed as one of the "illegal" publications by the

Lithuanian National Archives, probably published between 1894 and 1899.

The struggles of the book-carriers have been praised in modern times by

Father Julijonas Kasperavicius who said: "The work of restoring

Lithuania's independence began, not in 1918, but rather at the time of the

book-carriers. With bundles of books and pamphlets on their backs, these

warriors were the first to start preparing the ground for independence,

the first to propagate the idea that it was imperative to throw off the

yoke of Russian oppression." In any other country a smuggler as an

ancestor would probably be cause for embarrassment but, as the son of a

Lithuanian "smuggler" of the 19th century, I have no sense of

shame or embarrassment. The very opposite, for I have a heartstirring

pride that my immediate ancestor was one of the warriors described by

Father Kasperavicius and had been a hero - however minor - of his country

and his, and his many colleagues' exploits are part of the folklore of his

native land.

-

- John Millar (Jonas Stepsis) is a regular

contributor to Lithuanian Heritage living in Fairlie, Scotland.

Recently he was awarded a Winston Churchill Fellowship which allowed him

to travel to Lithuania to research the history of the

"book-carriers." The only extant photograph of Vincas Stepsis

(a.k.a. William Millar - rear), taken in 1930 in Scotland, with his

family. Next to him are his wife Petronele (formerly Domeikiene) and

Joseph Domeika. The author (aged 7) is in the front row, accompanied by

sister Mary (on knee), half-sisters Alice and Ann, and half-brother Peter.

|